Interview conducted by LocalsGuide.

Water is one of the most precious resources on our planet, yet many modern water management practices have dramatically altered its natural cycle, contributing to increased drought, desertification, and fire risks. Jenny Kuehnle and Alicia Vlass, of Ahimsa Gardens LLC, and some of their coworkers are on a mission to change that through the practice of “slow water.” By designing rain gardens and implementing water retention strategies, Ahimsa Gardens is working in Southern Oregon to create healthier soils, resilient plant life, and fire-resistant landscapes. In this interview, Jenny and Alicia share insights into the significance of slow water, the ecological impact of rain gardens, and simple ways that many people can contribute to restoring balance to our environment.

Hi Jenny and Alicia, thank you very much for taking the time to speak with us today! To begin with please tell us about your business Ahimsa Gardens and the work you are doing here in Southern Oregon.

Jenny: Hi Shields, I started Ahimsa Gardens in 2016 with a small crew. We have grown a lot, especially in the last 5 years, due to the incredible crew that we have. We have 16 employees including master stone masons, skilled carpenters and welders, irrigation technicians, conscientious maintenance workers, an in house designer, and an office manager who holds everything together. I am truly grateful for all of my co-workers and enjoy watching everyone’s interests and expertise expand in the work setting. My co-worker Alicia Vlass, who joined Ahimsa in 2022 is here with me for this interview, as the topics that we will be discussing are passions of hers as well.

Alicia, please tell us about the concept of “slow water,” and why is it crucial for a healthy and balanced ecosystem?

Alicia: Water is dynamic, moving through earth’s major water reservoirs. Oceans hold about 97% of the earth’s water; ice and snow are the second largest reservoir; then groundwater and surface water are the third largest reservoir. The natural flow of water moves through high altitude grasslands and forests, wetlands and floodplains. The groundwater and surface water are two parts of the water cycle that we can engage with and learn from. Slow water is a key concept in a healthy water cycle. Conservation biologist Brock Dolman explains slow water through the phrase ‘slow it, spread it, sink it, store it and share it’ – all with the intention of maintaining clean, sustainable water patterns and flows. Groundwater is stored below the earth’s surface, residing within porous rocks and sediments and filling space in between soil particles. Lakes, rivers and wetlands are identified as surface water. The phrase ‘slow

it, sink it, spread it’ is highly applicable to these types of water, and we can influence the quantities of water storage in many different ways; rain gardens and bioswales are two tangible examples of slowing and sinking water on an urban landscape scale. To understand slow water, we must also recognize ‘fast water.’ In urban environments, humans typically divert water into quick, narrow impermeable pathways

which contrasts wildly with water’s true nature. The fast speed at which we typically move water through human developments contributes to soil dehydration and water cycle disruptions, leading to climate

catastrophe. Our disconnect from water has created fragmented ecosystems that are struggling deeply. Water is a vital resource for all life on earth. Changing water’s course and pace directly affects all beings, ecosystems and climate patterns. Not only does ‘slow water’ help with soil hydration but it also helps with fire resilience. Please say more.

Jenny: Humans have drastically impacted and altered the land we live on, through urbanization, altering natural drainage pathways, grading and excavation, deforestation and vegetation reduction,

paving and creating impervious surfaces, dam construction, and pollution. Reduced soil coverage by vegetation leads to erosion, destruction of soils, and ultimately, desertification of once lush ecosystems. The impermeable surfaces of urbanization inhibit ground water recharge. Many modern agricultural practices utilize irrigation practices that deplete groundwater reserves. Slow water practices, on the other hand, support soil hydration, healthy soils, and an intact water cycle. Larger quantities of water

stored in groundwater reserves support diverse plant and soil life, keeping plant life green, hydrated, and less flammable. Thriving plants and living soils directly correlate to a more fire resilient landscape. Beavers play a significant role in creating a fire resilient landscape, as their dams slow and spread out water into the soils like a damp sponge. This encourages groundwater recharge which directly influences how prone a landscape is to wildfire. Hydrated areas with healthy beaver activity are a safe refuge for many species during wildfires.

Can you explain the historical impact of human activity on soil hydration and desertification?

Alicia: For a simple example of human activity influencing the water cycle and soil hydration we can turn to green and grey infrastructure.Grey infrastructure includes the human created aspects of a water system like pipes, spring boxes, wells or dams. Green infrastructure refers to the natural aspects of

our water systems such as forests, wetlands, rivers, and riparian zones. In general, implementing green infrastructure, and finding nature based solutions can be more cost effective than grey infrastructure, and is supportive to the water cycle. Soil hydration is supported by slow water practices. On the contrary, desertification, by removing water from land as quickly as possible, is a land degradation process that minimizes soil biodiversity and water capacity to the point of desert-like conditions. There are an immense number of causes, human activity being a significant contributor. How we relate to water, soil and all living systems is crucial. To lean on the wise words of Indigenous scientist Robin Wall Kimmerer, all flourishing is mutual.

How do rain gardens work, and what are their key benefits?

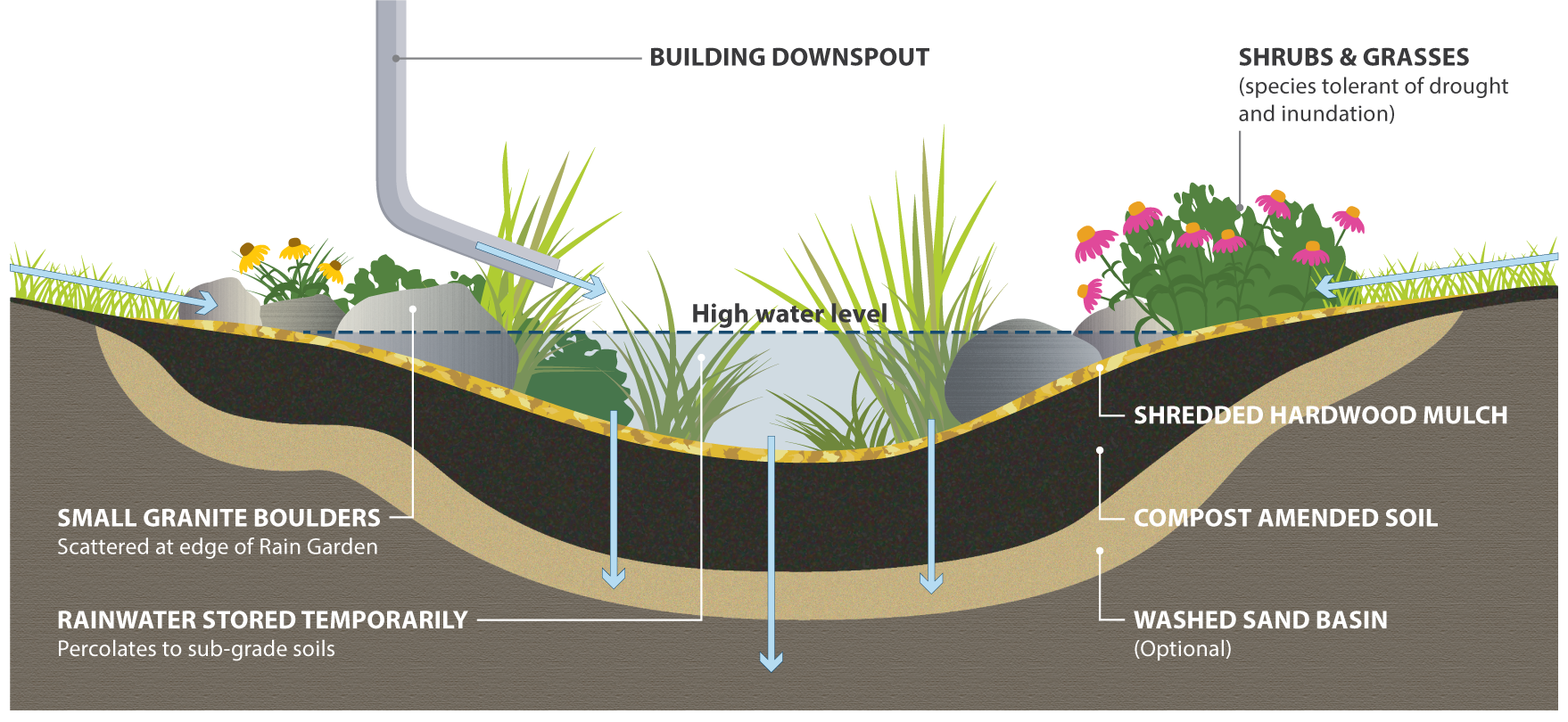

Alicia: Rain gardens are a great way to slow down water and recharge underground aquifers in an urban setting. Rain gardens are a depression in the land that are created to collect, slow, spread and sink storm water runoff into the soil. They are planted with a variety of plants, which filter pollutants through a process called phytoremediation. Rain gardens and bioswales reduce flooding and support the ground water by allowing the water to percolate directly into the soil. By building healthy soils and healthy plant communities, rain gardens also reduce flooding in local streams. Rain gardens filter sediment and pollutants through nutrient cycling or by sequestering pollutants in the soil or in the plants themselves. Rain gardens cleanse, detain, and reduce runoff by allowing water to seep into surrounding soil. Rain gardens are a practical example of “slow it, spread it, sink it” by diverting water back into the soil to help feed the groundwater to build soil hydration rather than into storm drains that quickly funnel water down impermeable surfaces.